Exploring Environmental Psychology for a Successful Sustainable Future

Introduction to Environmental Psychology

Environmental psychology is a subfield of psychology that examines how people interact with their environment and how their surroundings affect their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

Psychological Effects of The Environment

Nature typically comes to mind when people think about the environment. But in environmental psychology, the term “environment” encompasses both natural and artificial contexts. ‘Human-made environment’ can relate to everything from businesses and classrooms to schools, hospitals, neighbourhoods, and even spaces inside the house. Typically, natural habitats include the great outdoors.

Although there are many environmental aspects in psychology, “environmental psychology” generally refers to how people interact with their surroundings. These include the calming effects of natural environments, other aspects of wellbeing in man-made spaces, such as how wellbeing can be maintained in offices, homes, and schools, as well as the positive or negative effects of spaces on people who occupy them (including the impact of environmental stressors, such as crowding or excessive noise).

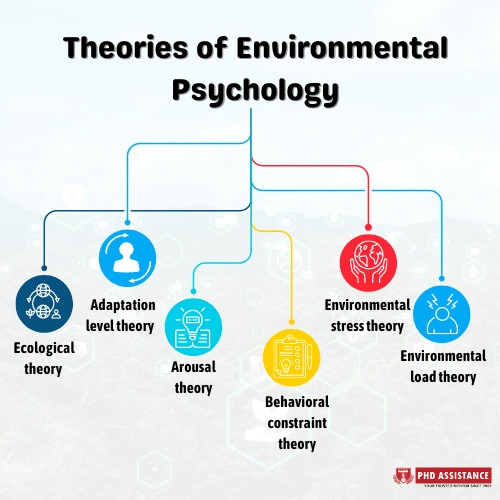

Theories of Environmental Psychology

Six environmental psychology theories are regularly utilized.

- Ecological theory

Ecological theory suggests a symbiotic relationship between a person and their environment, where a person’s behaviour may not change if their environment changes. Roger Barker’s study on students’ behaviour in small and large schools revealed that those who took on multiple roles in smaller schools were equally interested in taking on different roles in larger schools.

- Adaptation level theory

The Adaptation level theory suggests that people adapt to a certain level of stimulation from their environment, with a ‘right’ amount of stimulation. A classroom study found that children were more disruptive when the teacher ratio was high while less disruptive when it was low. The ‘right’ ratio was 18-22 children per teacher. This place attachment theory interior design impacts how much stimulation people need to act in desired ways and helps environmental psychology examples understand why people may not prioritize environmentalism and sustainable future ideas in their daily lives.

- Arousal theory

Arousal theory suggests that people’s behaviour is influenced by their psychological arousedness by their environment. It suggests that individuals have an optimum level of excitement, and their behaviour changes based on this level. Those with higher arousal tend to engage in riskier behaviours, while those with lower levels are more satisfied with less exciting or risky situations. This theory has significant implications for place theory psychology definition of environmental Phd Dissertation psychology theory, as individuals with lower arousal levels may be less motivated to change their behaviour.

- Behavioural constraint theory

Behavioural constraint theory suggests that individuals may react to stress by escaping it or coping better with it. This theory can be applied to populations affected by climate change, such as those in flood-prone areas. Some may move to other areas, while others focus on flood-proofing their homes. Some may choose to do nothing at all, feeling powerless and unable to change due to the global phenomenon personally.

- Environmental stress theory

Environmental stress theory suggests that people respond to external stimuli, whether real or imagined, as a threat. Extreme stress can lead to negative reactions in future situations, as seen in bushfires, where hot weather and wind can trigger stress regardless of the threat.

- Environmental load theory

Environmental load theory suggests that humans can only process a certain amount of information at a time, leading to tunnel vision for certain ideas. This can lead to focusing on incorrect information and ignoring counterarguments. For instance, social media’s distribution of climate change denial information can create a vortex where people see and believe only information that supports their current worldview, highlighting the dangers of tunnel vision in the environmental realm.

- Check out our study guide to learn more about Phd manuscript study guide

Psychological approaches to environmental transformation

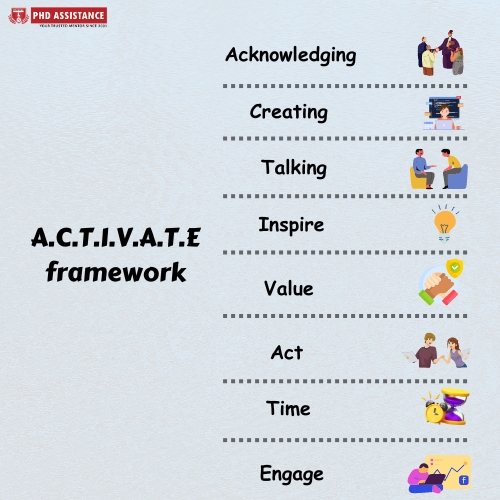

While climate change has many negative psychological effects, psychology may also be utilized to understand better why some individuals do not live sustainably and to urge them to do so. The Australian Psychological Society, for example, has introduced the A.C.T.I.V.A.T.E. framework, which is intended to assist individuals in addressing and coping with climate change stresses while remaining active in advocating for sustainability. The abbreviation stands for:

- Acknowledging feelings about climate change.

- Creating social norms about living sustainably.

- Talking about climate change.

- Inspire visions for a sustainable future.

- Value your commitment to sustainability.

- Act individually and collectively towards solutions and engagement.

- Time to advocate for sustainability is now.

- Engage with nature to keep your spirits up.

Future Directions and Challenges

Research design has demonstrated the benefits of immersion in natural environments on psychological well-being (Cox et al., 2017; Shanahan et al., 2016). For example, Shanahan et al. (2016) discovered that visits to natural places were related to lower community rates of depression and high blood pressure. In contrast, Lee et al. (2011) found that exposure to a forest setting vs an urban environment significantly boosted the strength of pleasant sentiments while decreasing negative feelings. Negative affect and stress reduction, anxiety reduction, increases in pleasant emotions, attention restoration, enhanced creativity, and mortality reduction have all been discovered to be advantages of nature immersion.

The current study demonstrates that transformational learning theory may aid in the design and implementation of educational interventions as well as learning assessments toward sustainability by assessing the learning process, outcomes, and conditions in the core sample of studies and provides a better understanding of how the concepts and mechanisms of transformative learning theory are operationalized in sustainability learning and education for sustainable development (ESD) research, as well as encouragement for researchers and practitioners working to make sustainability education, teaching, and learning more transformative.

Conclusion

Environmental psychology is a vital field that reveals the relationship between human behaviour and the environment, offering insights for driving positive change. Understanding cognitive, emotional, and social factors can help design interventions promoting pro-environmental actions. This field equips us with tools to address global challenges and create a harmonious coexistence between humanity and the planet. To conclude, there is still no evidence focusing on how to promote Psychological approaches to environmental transformation.

Learn more about current publications and then seek Journal of Environmental Psychology’s call for papers.

About PhD Assistance

Our Phd experts provide end-to-end services, including rewriting your manuscript (translating your ideas into research paper), involving statistics and programming, editing and proofreading, formatting according to different journal styles, and submission. PhD Assistance is useful in revising the manuscript work in response to the reviewers’ suggestions. We reply to reviewer suggestions line by line and section by section, and we completely update the paper, including fixing any odd English phrasing.

References

- Bonnes, Mirilia, and Marino Bonaiuto. “Environmental psychology: From spatial-physical environment to sustainable development.” Handbook of environmental psychology(2002): 28-54.

- Uzzell, David, and Nora Räthzel. “Transforming environmental psychology.” Journal of Environmental Psychology3 (2009): 340-350.