How to Select a PhD Research Topic?

How to Select a PhD Research Topic?

Selection of relevant PhD research topic

Recent Post

Introduction

Selecting an appropriate PhD research topic is a starting point in a doctoral process. A clearly defined and unique research topic not only adds to the body of knowledge but also maintains the doctoral candidate’s interest and motivation over a period of intense Academic mentorship spanning many years. Luse, Mennecke, and Townsend (2012) state that the selection process must balance personal interests, academic significance, feasibility, and uniqueness. This paper distils evidence from academic literature to offer a systematic process for the identification and development of a PhD research topic

Example topics:

- Topic 1: User Acceptance of AI-Blockchain-Based Electronic Health Records Management System Enhanced: A Mixed method study.

- Topic 2: Factors influencing Blockchain Acceptance, Adoption, and Integration in Healthcare: A User-centric Acceptance Model Perspective.

- Topic 3: Patient-Centric Blockchain and AI application: Evaluating User Acceptance and Satisfaction in Healthcare Sector using PLS SEM and ANN Approach.

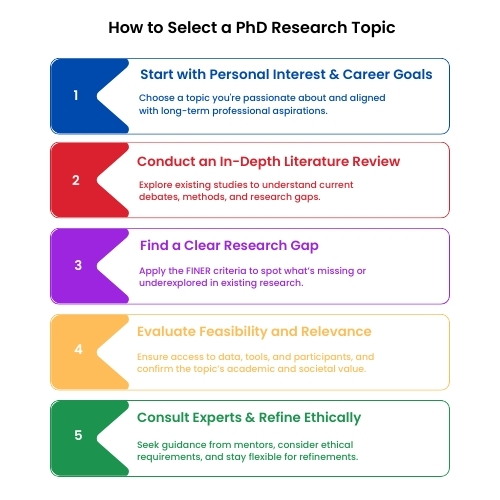

Personal Interests and Long-Term Aspirations

Personal interest is perhaps the most important factor in choosing a topic with Research originality. A doctoral course of study takes three to six years on average; hence, a strong underlying passion for the topic can assist in maintaining motivation during difficult periods. Luse et al. (2012) also argue that students who select areas that relate to their long-term goals and areas of interest are more likely to succeed in their courses. In the same line, Phillips and Pugh (2010) recommend that one should think about career goals, their own goals, and intrinsic motivation before deciding on a research topic [1] [2]

Conduct an Extensive Literature Review

A systematic literature review enables students to grasp the terrain of ongoing research, such as prevailing debates, prevailing theories, and methodological trends. It is also useful in determining gaps to be filled by new research (Boote & Beile, 2005). Literature review is not a fixed entity; it is an evolving process that dictates the course of developing the research topic over time. Through analysis of what has been studied before, researchers are able to avoid duplication and work towards making new contributions [3].

Determining Research Gap

Finding gap is crucial for meaningful and original research. Original does not mean coming up with something from scratch, since Rowley and Slack (2004) argue that it may involve applying established theories in new settings, bringing two fields together, or discovering overlooked problems. The FINER criteria—Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant—can be a great checklist at this point [4] [5].

Example topics:

- Topic 1: User Acceptance of AI-Blockchain-Based Electronic Health Records Management System Enhanced: A Mixed method study.

- Research gap: While blockchain technology shows promise in healthcare, studies often overlook the specific factors influencing adoption and integration among healthcare professionals and patients.

- Topic 2: Factors influencing Blockchain Acceptance, Adoption, and Integration in Healthcare: A User-centric Acceptance Model Perspective.

- Research Gap: While blockchain technology shows promise in healthcare, studies often overlook the specific factors influencing adoption and integration among healthcare professionals and patients.

Consider Feasibility and Scope

Make it Academically and Practically Relevant

Relevance of a topic goes beyond academia. A suitable PhD topic frequently resolves a critical issue of society or addresses a gap in knowledge that has practical consequences. Walden University (2020) emphasizes that effective research tends to be theoretically informed and practically relevant. Applicants need to ask themselves if their research can have an impact on policy, inform industry practices, or enhance well-being at the community level.

Consult Experts

Define Ethical Implications

Refinement

Conclusion

References:

- Luse, A., Mennecke, B., & Townsend, A. (2012). Selecting a Research Topic: A Framework for Doctoral Students. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7, 143–152. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274071371_Selecting_a_Research_Topic_A_Framework_for_Doctoral_Students

- Phillips, E. M., & Pugh, D. S. (2010). How to Get a PhD: A Handbook for Students and Their Supervisors. McGraw-Hill Education. https://lahore.comsats.edu.pk/library/hub/How_to_get_PhD.pdf

- Boote, D. N., & Beile, P. (2005). Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educational Researcher, 34(6), 3–15. https://writing.uwo.ca/img/pdfs/Scholars%20Before%20Researchers.pdf

- Rowley, J., & Slack, F. (2004). What is the future for knowledge management? A view from the UK. International Journal of Information Management, 24(2), 121–138. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242093125_What_future_knowledge_management_users_may_expect

- Hulley, S. B., Cummings, S. R., Browner, W. S., Grady, D. G., & Newman, T. B. (2013). Designing Clinical Research. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. https://tilda.tcd.ie/epidemiology-biostatistics-course/course-material/assets/Class2/Designingclinicalresearch_4th-edition.pdf

- Olalere, A. A., De Iulio, E., Aldarbag, A. M., & Erdener, M. A. (2014). The dissertation topic selection of doctoral students using dynamic network analysis. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 9, 85-107. Retreived from http://ijds.org/Volume9/IJDSv9p085-107Olalere521.pdf

- Lovitts, B. E. (2005). Being a good course‐taker is not enough: A theoretical perspective on the transition to independent research. Studies in Higher Education, 30(2), 137–154. https://sci-hub.se/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500043093

- Resnik, D. B. (2011). What is ethics in research & why is it important? National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/bioethics/whatis